.gif)

.gif)

Manteo, a chief of the Croatan tribe, and Wanchese, a Roanoke, were Algonquian-speaking Indians in what is now coastal North Carolina. Two of the earliest American Indians to enter into the English record, Manteo and Wanchese were integral to the establishment of Anglo-Indian relations at Roanoke, the first English experiment with permanent settlement in America. Manteo and Wanchese returned to England with a reconnaissance party sent by Sir Walter Ralegh in 1584 after having received a grant from Queen Elizabeth for exploration and colonization in Virginia. The sources are silent on how Ralegh’s agents managed to coax the two men to return with them. It is unknown, and unlikely, that the two knew each other, and it was not long before the two Indians found they had little in common; Manteo maintained a friendly relationship with the English during his stay in London and beyond, whereas Wanchese became hostile toward a people he considered to be his captors soon after his arrival in England.

When Manteo and Wanchese arrived in London, they were guests of Ralegh at his residence, Durham House. While there are no surviving records of their first days in London or the reactions of the locals, one can imagine that the two groups must have been a curious sight to the other. Ralegh kept tight control of Manteo and Wanchese’s schedule, and had his guests dress in the English fashion so as not to draw more attention to them. A German gentleman who was able to meet the two visitors noted that “[t]heir faces as well as their whole bodies were very similar to those of the white Moors at home,” and that he thought “they had a very childish and wild appearance.” Manteo and Wanchese were to become an integral part of Ralegh’s propaganda plan for Virginia, first by drumming up financial support and volunteers for the envisioned colonies, and second, by providing unparalleled insight into the indigenous people of southern Virginia and their culture.

The linguistically-talented Thomas Hariot was tasked by Ralegh with learning the Algonquian language and creating a detailed dictionary. To help him and other Englishmen become bilingual, Hariot developed an alphabet of thirty-six symbols in which "to expresse the Virginian speche" and any other spoken language from the Americas or Europe. Hariot sat down with Manteo and Wanchese daily to glean as much information as he could about the region around Roanoke Island and the tribes that inhabited it. Through Manteo especially, and to a lesser extent, Wanchese, the English were able to learn a great deal about Indian warfare, religion, and land in preparation for Ralegh’s first English outpost on Roanoke Island.

After about eight months in England, Manteo and Wanchese returned to Roanoke among the second expedition financed by Ralegh to southern Virginia. Upon their return home, the two men’s place in history diverges. Manteo, serving as an interpreter and guide, fulfilled Ralegh’s hopes for him by helping the English establish friendly relations with the local tribes. Although he is not always mentioned in the records of subsequent reconnaissance missions, his knowledge would have been indispensable to the English in their interaction with the inhabitants of Roanoke Island and the mainland. Meanwhile, Wanchese immediately rejoined his people on Roanoke Island. One can only speculate about the reasoning behind his decision: he may have felt ill-treated by the English or resented Manteo, who was from a different tribe and higher status. Or possibly Wanchese, after his visit to England, saw in the colonists a serious threat to his people, who, unlike Manteo’s tribe at Croatan, would be neighbors to the English and competitors for the island’s limited resources. Speculation aside, Wanchese returned to the Roanoke and is not mentioned again in the English record.

There are, however, numerous references to Manteo’s continued presence at Roanoke. Manteo served as an interpreter for two colonial leaders, Richard Grenville and Ralph Lane, in their initial explorations of the Virginia coast. Manteo’s loyalty proved invaluable. For example, during a scouting party into hostile territory, Manteo was able to warn Lane that the sounds of Indians singing on the riverbank was not, as the Englishman thought, a warm welcome, but rather a war cry. A volley of arrows soon followed their song, and Lane avoided a dangerous ambush because Manteo was there to translate. Manteo continued to provide essential linguistic and diplomatic aid to the English that made their brief stay in Roanoke possible.

Manteo’s most significant contribution, perhaps, was his assistance to John White, a watercolorist sent to the colony with Hariot. White created a remarkable series of about 75 drawings of the flora, fauna, and the Algonquian people who inhabited the Outer Banks region. His drawings, still considered by many to be the most authentic images of Early America’s indigenous people, captured intimate scenes of Algonquians, their dress, towns, fishing techniques, agriculture, ritual dances, and ceremonial figures, unlike anything possible without the knowledge and access provided by someone like Manteo.

In June of 1586, Sir Francis Drake arrived at Roanoke and offered the remaining colonists a return voyage to England that was readily accepted on account of a depleted food supply and increased tensions with the local tribes. Manteo went with them, returning to England for the second time. Manteo, now accustomed to the English language and culture, worked with Ralegh, Hariot, and future Roanoke governor John White on plans for a new English settlement in southern Virginia. Cordial relations with their Indian neighbors would be crucial for the new settlement; women and children would be included, making Roanoke a legitimate colony, not just a military outpost. As before, Manteo would be crucial to the English’s peacemaking plans.

Manteo returned to Virginia in May 1587, alongside 114 perspective colonists. Soon after their return, White sent about twenty of his men, accompanied by Manteo, to Croatan to learn whether the tribe intended to maintain friendly relations with the English. At the sight of Europeans, the Croatans prepared for battle. "Then Manteo their countreyman, called to them in their owne language, whom, as soone as they heard, they returned, and threwe away their bowes, and arrowes, and some of them came unto us, embracing and entertaining us friendly." Manteo’s presence once against proved indispensable for the English. Manteo’s kinsman offered to come to Roanoke and arrange a meeting on behalf of the English with other tribes to sue for peace.

When the expected negotiations failed to happen on schedule, White decided to retroactively punish the neighboring Roanoke tribe for the deaths of about twenty Englishmen between 1585 and 1587. On August 9, White dispatched a force of twenty-five men, which included Manteo as a guide, to seek out the Roanoke for revenge. Manteo and the English crossed to the mainland and assaulted a group of Indians at Dasemunkepeuc, killing one Indian and wounding several. Unfortunately, the victims turned out to be Croatans, Manteo’s people, rather than Roanokes. This unfortunate event was one of many that highlighted the difficulty of Manteo’s position as a cultural intermediary between two groups and two different cultures. Although White later recalled that Manteo did not hold the English at fault but instead his own people for failing to successfully establish peace negotiations, he surely must have felt the weight of his decision, and likely guilt, in siding with the English over his own people.

So efficiently was Manteo acclimated to English life that a few days following the military disaster at Dasemunkepeuc, he became the first Indian convert of the Anglican Church after his baptism in August 1587. In an empty gesture Ralegh wrote from England that Manteo was to be the ruler and representative of all the surrounding Indian groups. Thus his baptism seems more likely a political move orchestrated by Ralegh than an important religious conversion for Manteo. He knew that the title held no value; the neighboring Roanoke were not Manteo’s people and they had not chosen him as a ruler.

Trying to establish Manteo’s whereabouts following the baptism ceremony is problematic, as no records survive for the period between White’s departure to England in 1587 to obtain supplies for the colony and his belated return in 1590. White’s recounting of his final expedition to Roanoke recognizes Manteo’s loyalty to both his people and the English as the only promising clue in the inexplicable disappearance of the remaining Roanoke colonists. White took comfort "that I had safely found a certaine token of their safe being at Croatoan, which is the place where Manteo was borne, and the Savages of the Iland [are] our friends.” Manteo may have left with the colonists following their abandonment of Roanoke and met a similar fate, or returned home to the Roanoke to live out his remaining days. Much like the Roanoke colony itself, the fate of Manteo was lost to history.

Bibliography:

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. Roanoke: The Abandoned Colony. 2nd ed. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007.

Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. “Roanoke and Its Legacy,” in Thomas Hariot A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia. The 1590 Theodor de Bry Latin Edition. Published for the Library at the Mariners’ Museum. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007, 1-7.

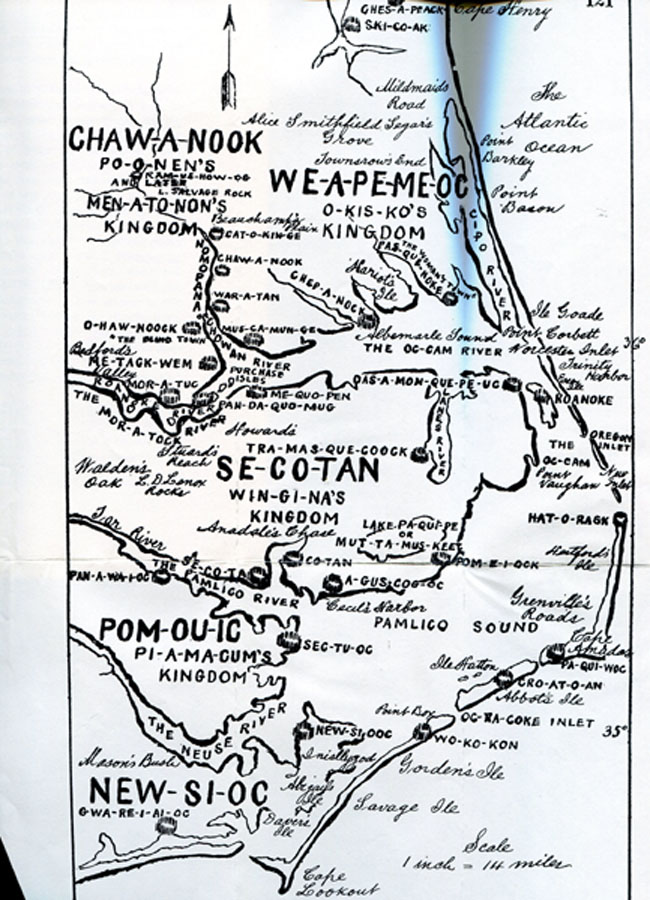

Sams, Conway Whittle. The Conquest of Virginia: The First Attempt. Spartanburg, South Carolina: The Reprint Company (map between pp. 76-77).

Milton, Giles. Big Chief Elizabeth: The Adventures and Fate of the First English Colonists in America. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000.

Vaughan, Alden T. "Sir Walter Raleigh's Indian Interpreters, 1584-1618." The William and Mary Quarterly 59, vol. 2 (2002): 341-376.

©Crandall Shifflett

All Rights Reserved

2014